I first read Jules Verne's Journey to the Centre of the Earth in a children's edition (much abridged, with an illustration on every facing page), and fell immediately in love with it. Secret subterranean worlds. Secret subterranean worlds with dinosaurs. When you're seven, things like this give literature purpose.

I'm a little older now, and I've given up on looking hopefully into caves (mostly), but Journey to the Centre of the Earth is still on my literature-to-escape-with shelf. 'Escapism' gets a reputation it doesn't deserve - as if reading about fictional dinosaurs meant dodging your civic and moral duty as a human being, honestly - and I'm proud of my literature-to-escape-with shelf, although it's worth stating that the fantasy-horror-and-SF shelves are separate. I wouldn't call something like Childhood's End escapist, and Ender's Game only in a worrying sense. (The Star Wars novels are in a grey area.)

My definition of 'escapist' doesn't relate to the book itself, I think, so much as what it's represented to me in the past. I never get tired of reading books like Journey to the Centre of the Earth or War of the Worlds because I remember what it felt like to read them for the first time, when 'What if...'s were even more powerful. 'Escapism' is far too simplifed a term for that kind of power. There's a great article on the significance of science fiction here, discussing why:

Let me convince you that SF does not originate from the changing world that surrounds us. It doesn't come from technology, it doesn't come from advancement, and it doesn't come from change. SF is independent of the world around us. SF comes from a place inside us, basic and primal, fundamental to our nature.

Think back to the time you were a little kid. Think back to age seven or six or five or four. The further back you can remember, the better.

When you're that young, every third thing is a brave and strange new world. Everything that lies behind the next corner may lead to a rabbit hole, to a new place, a new store with magical new things. Every new door may lead to a mysterious room. The next stranger you meet on the street may be a god or a devil or a Gandalf or God-knows-what. The next sentence that may be said to you, the next explanation you get about the world, may change everything you know, may turn your present understanding of the world on its head. When you're young, the world is full of giant possibilities that are completely outside the proverbial box.

At such a young age, we are, after all, still putting the world into explainable patterns. We still haven't figured everything out. And so anything might yet be possible. The world is unknown. The footing is uncertain. Everything hangs on a tether. Anything can change at any time. Everything can collapse, reverse itself, or reveal its true nature at any second. With every passing minute, you may discover that the world is actually different, that the rules you know are wrong, and that your explanation for everything that you know is utterly wrong.

That said, the book I really wanted to talk about here is Arthur Conan Doyle's

The Lost World (1912). Professor Challenger, the hero of this and a few other Conan Doyle novels, is a bad-tempered, self-centred, misanthropic scientist who makes a great read, even before the more fantastic parts of the narrative (dinosaurs, again; part of me is still that seven-year-old) make an appearance. The narrator's boss describes him as 'a homicidal megalomaniac with a turn for science', and he spends large parts of the expedition the story centres on squabbling with a rival, Professor Summerlee, to such a degree that the other adventurers make sure they're in separate canoes, a tactic that's only partially successful:

'Miranha or Amajuca cannibals,' said Challenger, jerking his thumb towards the reverberating wood.

'No doubt, sir,' Summerlee answered. 'Like all such tribes, I shall expect to find them of polysynthetic speech and Mongolian type.'

'Polysynthetic certainly,' said Challenger, indulgently. 'I am not aware that any other type of language exists in this continent, and I have notes of more than a hundred. The Mongolian theory I regard with deep suspicion.'

'I should have thought that even a limited knowledge of comparative anatomy would have helped to verify it,' said Summerlee, bitterly.

Challenger thrust out his aggressive chin until he was all beard and hat-rim. 'No doubt, sir, a limited knowledge would have that effect. When one's knowledge is exhaustive, one comes to other conclusions.'

I can't speak for all the other academics out there, but I've met these two before.

Although

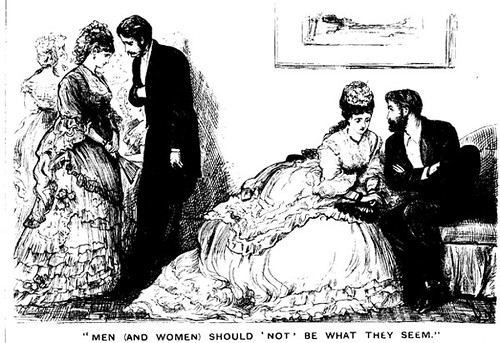

The Lost World has pride of place on my literature-to-escape-with shelf, I hadn't read it for a few years, and re-reading it recently gave a whole new resonance to one of the early scenes. After some bad experiences with the press, Professor Challenger has a habit of physically throwing journalists out of his house, and so Ned Malone, the story's narrator, tries another tactic to get an interview. With the help of his colleagues, he drafts a letter requesting a meeting:

'Dear Professor Challenger', it said. 'As a humble student of Nature, I have always taken the most profound interest in your speculations as to the differences between Darwin and Weissmann. I have recently had occasion to refresh my memory by re-reading–'

'You infernal liar!' murmured Tarp Henry.

'–by re-reading your masterly address at Vienna. That lucid and admirable statement seems to be the last word in the matter. There is one sentence in it, however, [...regarding which I] have certain suggestions which I could only elaborate in a personal conversation.'

Challenger replies, grumpily ('your note, in which you claim to endorse my views, although I am not aware that they are dependent upon endorsement either from you or anyone else'), and agrees to a meeting. The interview, however, doesn't go quite as Malone planned.

'I suppose you are aware, said he, checking off points on his fingers, 'that the cranial index is a constant factor?'

'Naturally,' said I.

'And that telegony is still sub judice?'

'Undoubtedly.'

'And that the germ plasm is different from the parthenogenetic egg?'

'Why, surely!' I cried, and gloated in my own audacity.

'But what does that prove?' he asked, in a gentle, persuasive voice.'

'Ah, what indeed?' I murmured. 'What does it prove?'

'Shall I tell you?' he cooed.

'Pray do.'

'It proves,' he roared, with a sudden blast of fury, 'that you are the rankest impostor in London - a vile, crawling journalist, who has no more science than he has decency in his composition! [...] That's what I have been talking to you, sir – scientific gibberish! Did you think you could match cunning with me – you with your walnut of a brain?'

And Ned, like so many journalists before him, finds himself somersaulting down Challenger's front steps.

The inclusion of a literal lost world, a plateau frozen in time and filled with dinosaurs and pterodactyls, make this escapist by most definitions. But for any young academics who've ever felt that 'oh God, look clever, or they'll discover I'm a fraud' feeling at conferences... well, I don't think Challenger himself is from that distant a place.